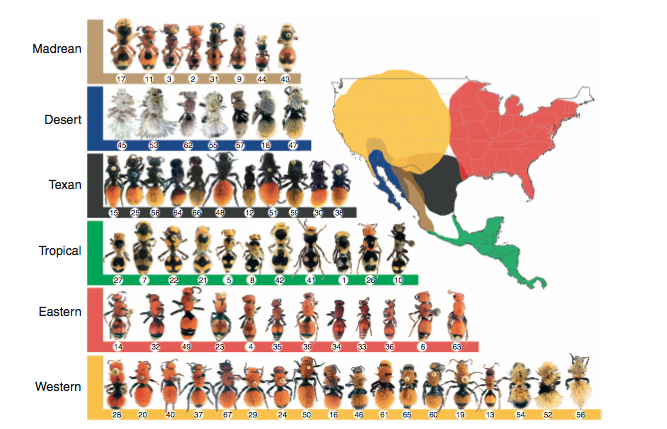

For this week’s installment of the “meet our bugs” series, we’re profiling a fascinating example of Great Basin biodiversity, our velvet ants. Despite their name, these cuties are actually wasps (Hymenoptera) in the family Mutillidae. Velvet ants are all solitary species, unlike many of the un-friendly wasps you might be more familiar with. Species of these wasps are found all over North America, though they are especially diverse in the arid West, and you can sometimes find them if you are hiking in undisturbed habitat. One feature almost all species share is the presence of aposematic coloration, or bright coloring that is meant to convey danger to potential predators. In the case of velvet ants, females are armed with a powerful sting, one of the most painful in North America! However, they are not aggressive and very rarely sting if unprovoked. As shown in the picture, many species in a given area will mimic each other to increase the protective ability of their coloration, a process known as Mullerian mimicry. So, it can be hard to identify individuals as different species; we do know that our wasps are all in the genus Dasymutilla.

Figure of Dasymutilla diversity in North America, along with associated mimicry rings (figure from Wilson et al. 2012). You can read more at the website of Joe Wilson at Utah State University Tooele.

Velvet ants have a number of interesting biological features. Males and females are extremely sexually dimorphic, meaning the sexes look very different. Sometimes, males and females of the same species don’t even share the same color pattern, making it hard to tell which species is which. In addition, females are all wingless (thus, all of ours are females), and are also the sex with a stinger; males fly and are harmless. One other characteristic of velvet ants is an extremely tough exoskeleton, which comes in handy for their lifestyle. Velvet ants share an unusual reproductive strategy in that they are ectoparasitoids of other solitary hymenoptera. A female velvet ant will locate the burrow of a solitary ground-nesting bee or wasp that contains a developing larva, invade the nest (often to the dismay of the host), and lay an egg next to the larva. The velvet ant egg will hatch into its own larva and proceed to kill the developing host, devouring it and/or any prey items in the burrow. However, once the velvet ant metamorphoses into an adult, the wasp will be a nectar feeder, visiting flowers during the morning and evening, making these species important pollinators of arid regions. Adult velvet ants can live for one to a few years, relatively long lived for wasps. Below are a couple short videos that demonstrate the nectaring behavior of velvet ants (the white ball is a cotton ball soaked in nectar solution).

In addition to the mimicry of velvet ant species to each other, other types of insects that may not be as well defended also mimic velvet ants to try and gain protection via association, a process called Batesian mimicry. These species include spiders, beetles, and antlion larvae. In fact, the spider mimic below was found right at the butterfly house, and we have seen velvet ants on the site as well. The unusual biology and ecology of these organisms, along with their diversity in the Great Basin, make them great species to exhibit at our butterfly house and outreach events.